Bradley Manning, collateral murder and the rise of data journalism

“If you had unprecedented access to classified networks 14 hours a day, 7 days a week for 8+ months, what would you do?”

--Bradley Manning

Where is the line between revealing sensitive information and reporting on gross human rights violations? The life of a young American depends on it.

In late 2009 Bradley Manning, a 22-year-old US army officer and intelligence analyst stationed in Iraq, came across a horrific video recording of US soldiers in a helicopter opening fire on unarmed local Reuters journalists and local citizens. He passed the video on to Wikileaks, a website that allows whistleblowers to make sensitive information public. The video came to be known as the Collateral Murder video. Manning also shared a great deal of information about the US occupations of Afghanistan and Iraq, including evidence of the torture of prisoners, civilian casualties, corruption, and shady negotiations in international diplomacy.

Wikileaks protects the identities of people submitting information, but Manning's identity was eventually revealed to the US's Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) by someone he had befriended online – a man called Adrian Lamo. Lamo believed that Manning's access to classified information was jeopardising lives because Manning was in a hostile war zone. The US military and administration concurred. Manning is currently in a US military prison and faces up to 22 charges that could result in a court martial, life imprisonment or even the death penalty.

The cache of information Manning turned over to Wikileaks were organised as three significant sets of documents, known respectively as the Afghan War Diary, the Iraq War Logs and Cablegate (based on US diplomatic cables). The Iraq War Logs were the basis for a remarkable evidence-based project called the Iraq Body Count Project.

Manning's disclosures led to one of contemporary journalism's most significant developments: the emergence of data journalism. The work of unravelling, decoding, analysing and piecing together all the information Manning passed on to Wikileaks was actually done by newspapers like The Guardian, Der Spiegel, Le Monde and others around the world. The Guardian, in particular, developed an entire section dedicated to data journalism, and the newspaper's journalists describe how they sifted through and made sense of the Wikileaks information through their Datablog. They say of their process: "When the Wikileaks releases exploded onto the news agenda last year, they changed many things - international diplomacy, the conduct of war and national secrecy. Perhaps lesser-realised is how they changed journalism. Wikileaks didn't invent data journalism. But it did give newsrooms a reason to adopt it."

Respected veteran journalist Philip Knightley, in his article Why Wikileaks changed journalism forever writes that the big struggle for journalists reporting on government has always been getting "the other half of the story" and "how to sort out truth from the propaganda". Thanks to the courage of unknown whistleblowers like Bradley Manning as well as advances in technology itself, there are now new ways of doing just this.

Join the global support network for the release of Bradley Manning.

FURTHER READING

WikiLeaks, Manning and the Pentagon: blood on whose hands? Al Jazeera, 2011.

Wikileaks data journalism: how we handled the data, The Guardian, 2011.

Dealing with Assange and the Wikileaks secrets, The New York Times, 2011.

The Data Journalism Handbook, Open Knowledge Foundation, 2012.

VIDEO

How Wikileaks changed journalism London, 2010.

LINKS & CAMPAIGNS

Bradley Manning campaign.

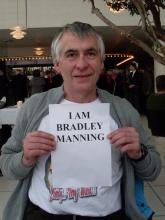

I Am Bradley Manning.