On not debating whether Twitter causes revolutions or not

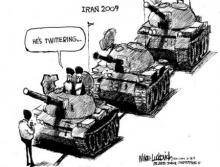

What makes people come together for a common cause and create large-scale social upheaval and change? One of the unexpected consequences of the political uprisings in Iran in 2009, and the Arab region in 2011, was a rather impossible-to-ignore debate about whether or not social media and digital technologies 'caused' revolutions in these regions. This question, however, is misleading, as it sets up offline politics, activism and resistance against the dynamics of digital communications technologies as if they were somehow disconnected.

What makes people come together for a common cause and create large-scale social upheaval and change? One of the unexpected consequences of the political uprisings in Iran in 2009, and the Arab region in 2011, was a rather impossible-to-ignore debate about whether or not social media and digital technologies 'caused' revolutions in these regions. This question, however, is misleading, as it sets up offline politics, activism and resistance against the dynamics of digital communications technologies as if they were somehow disconnected.

This reductionist portrayal of information technologies tends to mask other concerns we have about technology, like 'Does citizen journalism make traditional broadcast journalism obsolete?' and 'Can the virtual world take over the "real" world?'

Such concerns are ahistorical, and are based on a view of technology as something 'new'. In reality, technologies have long played a role in transmitting information in times of social change: the printing press in the French Revolution, audio cassettes in the revolution to depose the Shah of Iran in 1979 and public telephone booths in Apartheid-era South Africa. The reality is that the technology device itself is of little importance. Finding innovative ways to communicate with them is, rather, a fundamental part of organising dissent and rebellion, whatever the form this innovation takes.

Leaders of the April 6 Egyptian Youth Movement talk about the communicative role taxi drivers played in the Egyptian Revolution, spreading information to places where digital communications technologies weren't available. It is also now acknowledged that it was only when Hosni Mubarak shut off access to internet services and mobile communications that the revolution actually gathered momentum across Egypt. For it was when digital communications were cut off that most people got out on to the streets to share information and ideas, connect with each other and activist groups and stand together to demand change.

Zeynep Tufecki, a scholar of technology and society, says that we're "digital immigrants" trying to make sense of the interactions between technology and society. So the question is not “the shallow debate” about whether Facebook and Twitter can liberate entire nations, but what liberation itself means more broadly in the context of a networked culture. Tufecki urges us to also ask other questions, if we must talk about technology. “I think we need new literacies; people need to learn some basic things about the internet: What is TCP/IP? How does Google rank search results? Programmers understand that stuff – but then it must be combined with an understanding of people and societies as well.”

Tufecki is also calling our attention to the nature of the social media we use, their terms of service and use, the economic and political motivations of the companies that own them, and the commodification of our social relationships through our use of these media. The seeds of liberation may lie in what goes on behind the opaqueness of a Like button.

FURTHER READING

Techno-sociologist Zeynep Tufecki talks to The European about media, technology and society, The European, 2012

Leaders of the April 6 Youth Movement in Egypt reflect on what happened on the ground in 2011, The Eagle 2011

An individual describes the interplay between offline and online actions when he was arrested for fly-posting a sticker criticising the Egyptian military in “Things I've Learned from the Mask of Freedom”, Rolling Bulb, 2011.

VIDEOS

Manuel Castells speaks about Social Movements in the Age of the Internet, 2011

Geeks and Tweets: What LOLCats Can Tell Us about Human Rights and the Internet, by Ethan Zuckerman